This blog was written by Julia Irion Martins, our University of Michigan Summer intern.

Keweenaw National Historical Park Headquarters by Andrew Jameson

On my second morning in the Keweenaw, I walked from the Thomas Hoatson mansion in Laurium to the buildings of the former Calumet & Hecla mining company, now the Keweenaw National Historical Park. I was on my first ever archival research trip and I was meant to be collecting information to write the Reader’s Guide for the Great Michigan Read’s 2021 selection, The Women of the Copper Country. I was in the phase of my research where I was terrified that nothing would come together: I’d read some articles, part of a book, and most of a dissertation on the Copper Country and the 1913 miners’ strike. And, to make matters worse, all I’d managed to do so far on my archival trip was wander around a locked building, thinking some historical truth would reveal itself to me and hoping nobody would ask me to please stop loitering.

I spent the first couple years of my PhD trying to construct an understanding of Brazilian culture and history through reading architecture and place in Brazilian film. I don’t know why I thought my way into researching the history of copper mining in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula would be anything other than thinking about place and architecture.

Put simply, place is important for the towns of the Copper Country because without the particular geological formations of the Keweenaw Peninsula, there would be no copper to mine and thus no “reason” for architecture and no “reason” to consider the Keweenaw a “place.” (“Reason” and “place” are in scare quotes because the Keweenaw was a place long before European colonizers stumbled upon it—the Ojibwa people have been in the area since 500 CE.)

Located 300 miles from the nearest major city (Milwaukee) and over 500 miles from either Detroit or Lansing, it seems hard for those of us in the Lower Peninsula to believe that, at one point, Calumet and its neighboring towns were the seat of industry and wealth in Michigan. Part of my task then, as the researcher and writer for the GMR Reader’s Guide, was to make clear that Calumet was once The Place to Be, that in its prime, it was not thought of as “disconnected” from cities like Milwaukee or Chicago or even Boston and New York.

As I lurked outside the Park Headquarters, the importance of place and built structure left the theoretical and academic realm because my fear came true: a woman–Ellen Schrader–walked out of the building and asked what it was that I was looking for. I explained that I was there to research the miners’ strike, particularly women’s involvement in the miners’ strike (which you’ll see is related to the architecture and place in the Reader’s Guide). Immediately, Ellen invited me inside and said, “Let me go find our historian.”

Turns out, my timing had been perfect: the staff of the Keweenaw National Historical Park had just finished one of their first back-in-office meetings since Covid started and the KNHP historian, Jo Urion Holt, was in her office and willing to chat.

When Ellen brought me to Jo, we all remarked something along the lines of “isn’t it nice to be back at the office, where you can bump into just the person you need!” This trip to Calumet was the first travelling I’d done since Covid started. For over a year, I’d been teaching and taking classes remotely, the vast majority of my encounters with people were completely planned and usually virtual. Place, as technological progress would have it, ceased to matter. Sure, this “progress” allows us to “be connected,” but we’re alone, distant and in separate places.

The 1913-1914 miners’ strike happened in part because of a refusal to accept technological progress wholesale. When the one-man drill was introduced, miners in the Keweenaw hesitated. While managers saw efficiency, profits, and safer working conditions (the two-man drill created a rock dust that causes silicosis, the one-man drill did not), miners saw danger. This danger was not directly from the one-man drill itself, but from what that drill represented: the atomization of workers and a workforce cut in half (miners no longer needed to work in teams of two, which was a safety mechanism in itself—if an accident happened, a miner’s partner could run for help). Technological progress, maybe, but progress for laborers and labor rights? I’d argue not so much—distancing workers, spacing them apart and keeping individuals in different places necessarily makes it harder to connect and unionize.

My surprise encounter with Jo, only possible because I was physically in Calumet and the staff at KNHP was phasing out of virtual work, is precisely what allowed all the pieces of my research to fall into place (no pun intended). I had discrete notes and documents and photos, but it was Jo’s private tour of the closed Visitor’s Center exhibit and KNHP archivist Jeremiah Mason’s three hour historical walking tour of Calumet that made Calumet feel like a real place.

Being in Calumet really scrambled how I think about progress and history. It would be easy to fall into some clichéd and—dare I say—exoticizing narrative of “it’s a town frozen in time, so well preserved…” This narrative assumes preservation is effortless: the result of being forgotten (in the case of Calumet, forgotten once C&H closed in 1968). In other words, my experience in the Keweenaw has shown me that “to progress” doesn’t necessarily mean to move forward, just as “to preserve” is not to move backwards.

Keweenaw by Julia Irion Martins

During our walking tour, as Jeremiah unlocked the door to his church—the church Annie Clemenc, leader of the strike, attended at the turn of the century—Jeremiah said that it took leaving Calumet to realize how unique it is. Most places in the US don’t look like Calumet (or Houghton or Hancock). Old buildings are deemed hazardous or unimportant, relics of a bygone era, and rather than working to restore or preserve them, new industries tear them down and build up something else. Often, that something else is hideous.

The push for active preservation efforts in Calumet began in the 1980s, when the famous Italian Hall—the site of a strike era tragedy—was torn down. The destruction of the building sparked a community conversation about preservation, galvanizing the establishment of the Keweenaw National Historical Park in 1992. Around the same time, Julie and Dave Sprenger bought the Thomas Hoatson mansion and began restoring it into the Laurium Manor Inn (where I stayed). There are countless other restoration and preservation projects going on: the Curto Building, the Union Building, the tiled flooring of the Calumet Village Hall (which had been covered up by carpet!), a large lecture-type hall in the local high school—all of these projects require archival research, consultation with experts, and adherence to the city’s Historic District Commission guidelines.

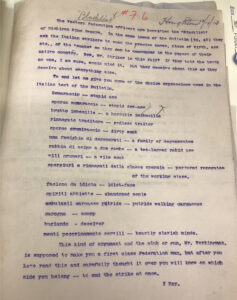

Photo taken at the Michigan Technological University’s Copper Country Historical Collections By Julia Irion Martins

To preserve the physical structures of a town helps us in preserving the events and memories of that town—that which we could argue makes a town a “place.” But to do this work, to “preserve” is not to try and return to a better or worse time. Rather, it is to do the difficult work of putting the present in conversation with the past. Obviously, there’s been tremendous social and economic change since the 1910s. But as I read The Women of the Copper Country, scholarship, and primary sources from the archives at Michigan Tech; as I spoke with specialists on the region; and as I simply walked around Calumet, I realized that the issues facing people in the 1910s are really not so different from today. We’re still facing problems surrounding xenophobia and racism, the movement and devaluing of industry, the depletion of natural resources, and anti-union policies. It’s not that history is doomed to repeat itself, but that history is in constant conversation with itself. (It does, of course, help when you find a list of insults Italian strikers threw at scabs… turns out that no matter the century, we’re all always thinking somebody is an “idiot-face.”)

This is a bit embarrassing to admit on the Michigan Humanities blog, but as a Coloradan I never even thought about Michigan (let alone the Upper Peninsula) until I came to graduate school at the University of Michigan. Even then, I’ve mostly thought about Michigan as “a place I have to be before I go to another place.” Generally, I think graduate students have a hard time feeling “placed” because of the assumption that as an academic you’re willing to go where the job is. Many of us, I think, expect that upon graduating we’ll be hopping from job to job, school to school—but never “place to place.” Even those of us who study architecture and place are socialized to think that location shouldn’t matter: Who cares where you are if the university is good? Who cares if the town looks good or has a sense of “self” beyond the university? You don’t “need” that if you’re at school. This sense of transience and disconnect often makes me feel anxious and hopeless. It makes me think I shouldn’t bother feeling invested in a place because it’s not a “place”—it’s simply “a university.”

Working with Michigan Humanities on the Great Michigan Read reminded me that location does still matter even if I’m “just here for school.” Learning about the history of the state (especially a part of the state that the majority of Michiganders rarely think about) made me feel much more connected to living in Michigan. Because of this internship and this research, I’m no longer a transient and disconnected grad student living in Michigan until I live somewhere else—I am in a place and not just at a school (even though Ann Arbor will never live up to the UP).

…

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities or Michigan Humanities.